Interdisciplinary Science Rankings 2025: results announced

There’s no silver bullet when it comes to interdisciplinary success, data from inaugural THE ranking show

Rosa Ellis Twitter: @RosaEllis

Browse the full results of the Interdisciplinary Science Rankings 2025

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) has topped the inaugural Times Higher Education Interdisciplinary Science Rankings, but the data suggest that there is no silver bullet when it comes to producing world-changing interdisciplinary science.

The US leads the way on cross-disciplinary scientific research, with seven institutions in the top 10 and 15 among the top 50.

The top 20 features 12 universities from North America, four from Asia, three from Europe and one from the Middle East.

The ranking – a project in association with Schmidt Science Fellows – uses 11 metrics to measure university performance in three areas: inputs (funding); process (measures of success, facilities, administrative support and promotion); and outputs (publications, research quality and reputation). The ranking was created to improve scientific excellence and collaboration between universities and aims to help institutions benchmark their interdisciplinary scientific work. Crossing traditionally narrow academic disciplines is widely seen as an important way to stimulate scientific breakthroughs and to help tackle some of the world’s most pressing challenges.

Top 10 universities for interdisciplinarity

MIT has an overall score of 92.4 out of 100, with 86.9 for inputs, 91.7 for process, and 94.2 for outputs.

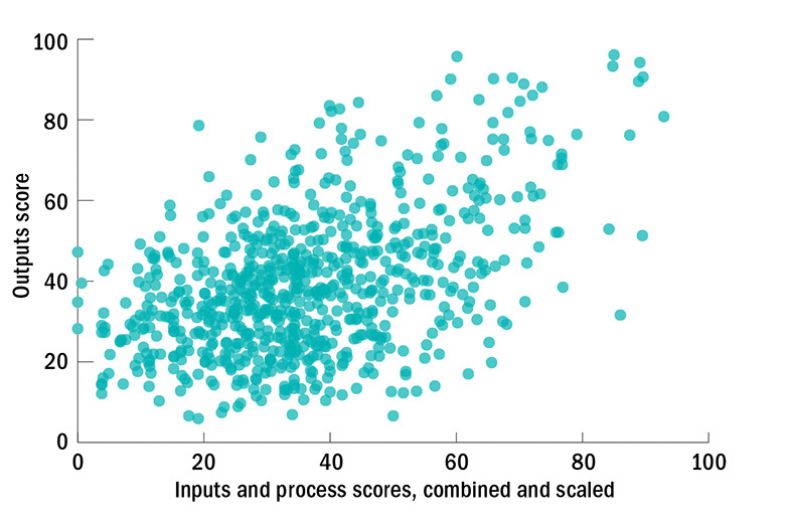

Analysis by THE’s data team found a correlation between the combined inputs and process pillar scores and the outputs scores, but no individual metrics with strong correlations. Billy Wong, THE’s principal data scientist, suggested that this means that each tactic – such as increasing funding for interdisciplinary science or including cross-disciplinary working in promotions criteria – is “necessary but not sufficient” to improve interdisciplinary science.

Correlation between interdisciplinary inputs and process and outputs

University leaders who spoke to THE said developing a culture that embraces interdisciplinary research was a vital, if complex, task.

Edward Balleisen is vice-provost for interdisciplinary studies at Duke University, an institution believed to be the first in the US to have a senior leader dedicated to the activity. He said interdisciplinarity was “a little bit like painting the Golden Gate Bridge. You can’t stop working on it – you have to have experimentation and be willing to do new things, but you also have to recognise that just because you’ve established a culture [it] doesn’t mean that it will remain vibrant.”

Duke, which ranks fifth in the table, has had interdisciplinary research as “an explicit strategic focus since the 1980s”, Professor Balleisen said. “We were never going to compete with MIT in certain fields. Directly through our disciplinary depth, we were not going to be challenging some of the very large public flagship universities that had three times as many students and twice as many faculty. So we had a recognition that there might be an opportunity for more impact through a strategic focus on interdisciplinary work,” he explained.

Duke employs a broad range of tactics to encourage interdisciplinary science, from interdisciplinary PhD programmes to joint academic appointments, physical facilities and promotions processes that recognise interdisciplinary achievements.

Recruiting leaders with an interdisciplinary mindset is essential, Professor Balleisen said. “No dean at Duke would be hired without meeting with me and other vice-provosts, and I’m going to be listening for that [interest in interdisciplinarity].”

Countries best represented in top 200

Cynthia Barnhart, MIT’s provost, attributed a large part of the university’s success in interdisciplinarity to the original design of the campus back in 1916.

“It was designed as one large, interconnected building, and the intention was to provide our faculty and our students – all of them – opportunities to bump into one another, to share knowledge and collaborate,” she said. “Then over the years, other structures, like labs and centres, institutes and, most recently, a college, have been created to enable and facilitate interactions across disciplines.”

Paula Hammond, MIT’s vice-provost for faculty, agreed that creating an environment and a culture that allowed spontaneous interactions was vital. “I have this feeling that I could bump into anyone in that hallway and start up a conversation and find a new collaboration or a new project or a new idea,” she said.

While university leaders talk of fostering a culture that encourages the cross-fertilisation of ideas, the academics THE spoke to were more concerned with career development. Several scholars undertaking cross-disciplinary research said universities needed to do more to support the careers of interdisciplinary scientists.

Flavio Toxvaerd, a professor of economics and public policy at the University of Cambridge who engages in interdisciplinary research, said it all came down to incentives.

“The interdisciplinary research output of universities relies on individual researchers choosing to engage in such research. But researchers respond to incentives; so if universities do little to change incentive structures, that will hold back progress on interdisciplinary work,” he said.

“Many universities profess to back innovative research that crosses boundaries, but when it comes to what can actually encourage such research, very little is done.”

Kirsi Cheas, founder and president of Finterdis, the Finnish Interdisciplinary Society, agreed that “academic evaluation practices still tend to promote disciplinary research, projects and positions, rather than allowing space for interdisciplinarity”.

“Many universities still have a long way to go,” she said. “Interdisciplinarity is often a buzzword that is abundantly and vaguely used in university strategies and solemn speeches, but the university leadership announcing such fine goals often does not sufficiently consider what kinds of resources are required for successfully implementing interdisciplinarity.”

Dr Cheas said some fields were better at encouraging interdisciplinary science than others. “In interdisciplinary fields such as sustainability science, inter- and transdisciplinarity is often the norm, and therefore, promotions processes and other practices can more easily manage to encourage interdisciplinarity. In other fields, the process is slower,” she said.

Despite the challenges that interdisciplinary working presents, all the university leaders who THE spoke to were in no doubt of its importance in solving wicked global problems.

How can we approach interdisciplinarity in higher education?

Edson Cocchieri Botelho, pro-rector of research at the Universidade Estadual Paulista (Unesp) in Brazil, said cross-cutting work was vital in middle-income countries that had many social challenges.

In Asia, the National University of Singapore (NUS), ranked third in the world for interdisciplinary science, is prioritising collaborations across disciplinary boundaries to address some of the world’s most difficult issues.

Liu Bin, deputy president (research and technology) at NUS, said interdisciplinary science was “integral to ensuring research remains cutting-edge and delivers impactful solutions where they are needed”.

The high level of participation in the inaugural Interdisciplinary Science Rankings – 749 universities from 92 countries and territories are included, making it THE’s biggest-ever debut ranking – can be seen as a reflection of the growing importance of interdisciplinary science. “The very fact that [THE] is recognising the significance of interdisciplinary work through a ranking is really exciting and validating,” MIT’s Professor Barnhart said.